Today, perhaps because I’m a little crazy, I’m starting to believe that I’m a very good writer. I never believed that before.

(interviewed by Rivista Studio in 2012)

Introduction

As the title of this section suggests, Gianni Clerici is, to all intents and purposes, ‘a writer on loan to sport’: this definition, which greatly annoyed him, came from Italo Calvino, the champion of refined writing. It is clear that, to be worthy of such treatment, Clerici’s work possesses qualities that do not escape the attentive and sensitive reader. His literary influences, which can also be deduced from the style of his articles, have a very specific direction: beyond French literature, which he discovered thanks to the advice of Gianni Brera, who was a translator, his main points of reference are British, above all Edward Morgan Forster, George Orwell, William Somerset Maugham, Wystan Hugh Auden, and his favorite, Evelyn Waugh. How can we forget the Americans and, of course, the best of the Italians: “My generation was shaped by Hemingway and Fitzgerald in translation, starting with Pavese and moving on to Fenoglio” (Roberto Andreotti and Federico De Melis, Wimbledon gioventù dorata, Il Manifesto, 26/06/2004); and again, “I stick to the methods of automatic writing of the Futurists, and of Marinetti, who came to die on Lake Como, in Bellagio. I start as if it were a letter, a note, and then everything comes naturally” (Il cantastorie instancabile, p. 90).

Before analyzing his work, it is worth quoting the preface to the first edition of The tireless storyteller: Gianni Clerici, writer, poet, journalist (Le Lettere, Florence 2010), an authorized biography written by Veronica Lavenia and Piero Pardini: “While the fame and fortune of the journalist and essayist have long since crossed national borders, earning him the highest accolades worldwide […], the same cannot be said for Clerici the writer. The author of rare short stories, the novelist with extraordinary irony, the poet, praised also by Giovanni Raboni and Attilio Bertolucci, has remained, in part, trapped in the limbo of journalists who are ‘aspiring’ writers. The fears raised by his illustrious ‘adoptive uncles’ Soldati, Bassani, and Brera, who were well aware of certain provincial aspects of Italy, were not unfounded” (p. 11).

Early career and first awards

Gianni Clerici’s literary career began in 1966. With the patronage of Giorgio Bassani and Mario Soldati, dear friends and exceptional proofreaders, Clerici presented his debut novel, Fuori Rosa, at the Strega Prize. (Vallecchi Editore, Florence), based on the football-set comedy Call girl. The reception of the work, in a context filled with skepticism for a journalist given to writing, turns out to be lukewarm, not to say cold: “The patroness of the Strega herself, Mrs. Bellonci, will go so far as to say to me, ‘But are you the same one who covers sports on the Giorno?’ That’s all she needed to add that I was doing the subjunctives correctly”(The indefatigable storyteller, p. 20).

Clerici therefore took a break, until the publication in 1974 of the triptych entitled When Monday Comes (Mondadori, Milan): in addition to the story that gives the collection its name, a “novel about the decline of a champion who goes to play in the provinces” (interviewed by Maurizio Crosetti, Repubblica, Turin), the book includes Altri Clown (new title given to Fuori Rosa) and I gesti bianchi (later renamed Costa Azzurra 1950). In the second cover of the first edition, Cesare Garboli, a friend of the author, summarizes a salient gift of the author thus, “Clerici knows the merciless art of objective storytelling.” Speaking of this collection, the display cases of the Archivio Luce preserve a curious interview of Clerici with his friend Giorgio Bassani, recorded on the occasion of the publication of the trilogy and aired within the newsreel.

Not only novels: in 1986 Clerici won the Vallecorsi Prize, a Pistoia award for theatrical works in prose and language, with Ottaviano e Cleopatra, a comedy to which he was very attached and for whose performance he had sought advice from Vittorio Gassman (see correspondence).

Despite his accolades, Clerici always spoke modestly about his theatrical works: “My failed plays have always produced novels. I consider myself a failed playwright” (Il cantastorie instancabile, p. 71).

In 1988, he published the Orwellian-inspired novel Cuor di Gorilla (Mondadori, Milan), originally titled Darwin contro Mango. The book introduces us to a light-hearted band of five chimpanzees who are given fake Italian citizenship so they can participate in the basketball championship. Behind the frivolous and irreverent appearance of the story lie anthropological questions and reflections on pedagogy and the human psyche.

Consecration

His international fame, already evident after the resounding success of 500 anni di tennis (1974), was consolidated in 1995 when Clerici published I gesti bianchi with the Milanese publisher Baldini e Castoldi. Oreste del Buono, director of the literature series, played a fundamental role in this collaboration, having worked tirelessly to promote Clerici’s reputation as a writer. The collection, which was reprinted several times over the years, consists of short novels set in the world of tennis: Londra 1960 (linked to Clerici’s years in London), Costa Azzurra 1950, and Alassio 1939. This last story, which recounts the genesis of Clerici’s childhood love affair with tennis on the eve of World War II, was translated into French in 2000 by publisher Viviane Hamy and received warm congratulations from then Prime Minister Lionel Jospin (see correspondence).

Also in 1995, Tenez Tennis, a play inspired by the exploits of the ‘divine’ Suzanne Lenglen, icon of tennis at the beginning of the century, was successfully staged at the Venice Biennale.

Two years later, Il giovin signore (Baldini Castoldi Dalai, Milan) was published, a coming-of-age novel in which the protagonist is constantly at the mercy of events, so much so that “the author seems to be engaged in denouncing and accusing his character’s flaws” (from the preface by Oreste del Buono).

With the advent of the new millennium, it was time for theater again: in 2000, Suzanne Lenglen. The Tennis Diva . Performed at the Teatro Belli in Rome, directed by Furio Andreotti and starring a young Paola Cortellesi, the play depicts the triumphs and conflicts of the athlete who changed the fate of women’s tennis forever with her style and her unconventional tenacity.

In 2004, it was the turn of Erba rossa (Red Grass). (Fazi Editore, Rome), a novel inspired by one of Clerici’s trips, which depicts, in the wake of several romantic entanglements, Prague in the 1960s, where, as the opening poem states, “Once the red grass has been mowed, green returns. But the most innocent strands are scattered” [V].

Recent years

Clerici made his poetic debut in 2005 with the collection Postumo in vita (Sartorio, Pavia). In the afterword, the author confessed that he had always been somewhat reluctant to publish his verses: “I have always written poetry, but in secret. While I have submitted myself to judgment in every other literary genre, I never found the courage to propose my verses to a publisher.”

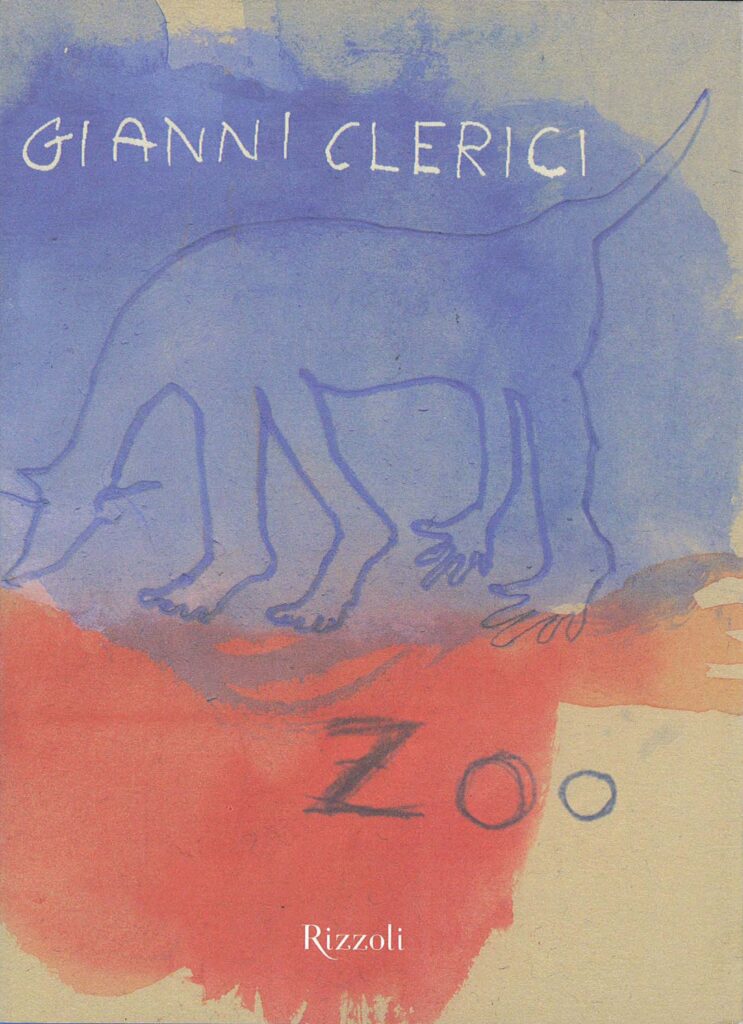

A year later, in 2006, Clerici published a collection of short stories. Zoo. Stories of bipeds and other animals (Rizzoli, Milan): in this collection of characters often inspired by real people, the author uses irony and sarcasm to outline the distortions of a sometimes beastly humanity. With Zoo, he won the Grinzane Cavour Prize.

In 2007, at the Teatro Valle in Rome, he staged Mussolini. The Last Night , Clerici’s most recent project as a playwright: the novel of the same title, published by Rizzoli in the La Scala series, is based on the text of the play.

He returned to short stories in 2008 with Una notte con la Gioconda (Rizzoli, Milan), a collection of twelve stories about extravagant characters linked to the theme of writing.

2011 was another year of poetry, with the release of Il suono del colore (The Sound of Color), his first collaboration with the Roman publishing house Fandango: here, as in the previous anthology, Gianni Clerici the person, rather than the author, shines through, with personal memories and intimate feelings.

A year later, Fandango published Australia Felix, a novel that addresses timeless issues such as the condition of ethnic minorities (in this case, Australian Aborigines) and the inconsistencies of Western civilization.

In 2017, he published Diario di un parroco del lago (Mondadori, Milan), in which Clerici recounts, through the words of a curate, anecdotes and secrets of the sfrosadòr, cigarette smugglers on the Swiss border. Of note is the skillful use of a hybrid language between Italian and dialect, which the author had studied in the texts of the poet Carlo Porta: “The great philologist Maria Corti believed that I wrote in a jargon she defined as ‘Lombardese’. That is, my own personal language, a blend of English and Lombard dialect. It is one of the most accurate things that has been said about my writing” (Il cantastorie instancabile, p. 23).

Published by Baldini & Castoldi, Gianni Clerici’s latest book dates back to 2020: the novel, entitled 2084. The dictatorship of women, tells the story of a dystopian future, where modern Amazons rule a world run by robots and supercomputers, in which human reproduction is strictly regulated and any form of creativity is viewed with suspicion. All this until the arrival of little Irma, who will turn everything upside down.