My people

will never again have

I am sure of this

a scribe like me

a tireless storyteller

one who loved the game

and knew everything

about those white gestures.

Journalistic career

The early years (1948–1956)

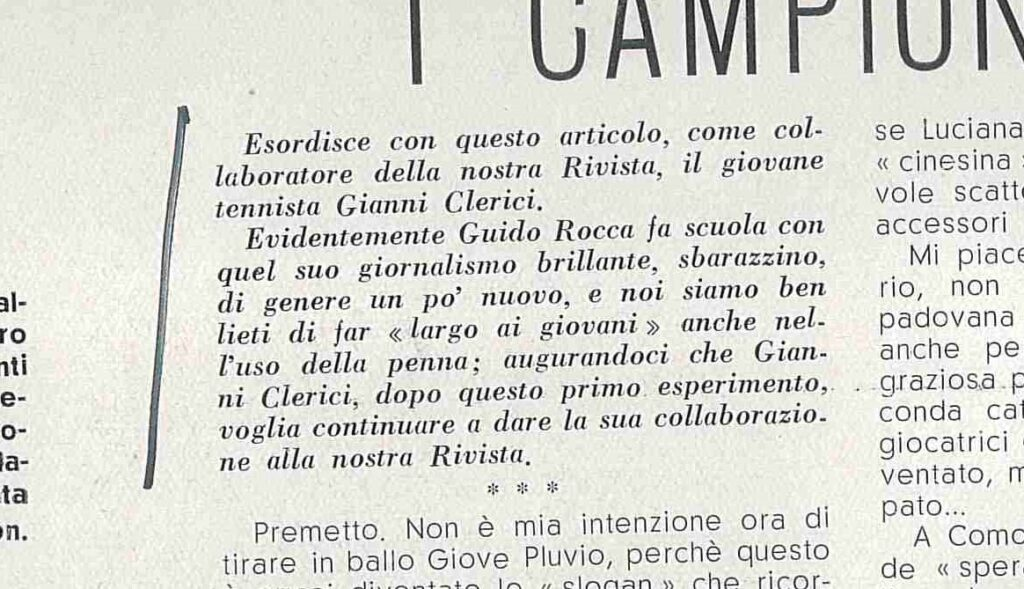

Clerici’s debut in the world of journalism dates back to August 1948: during the Italian second division championships, held in his hometown of Como, in which he participated in doubles with Vincenzo Mei, Gianni was appointed special correspondent by Umberto Mezzanotte, editor of the monthly magazine Il Tennis Italiano. His unmistakable writing style must have made an immediate impression, considering the editor’s enthusiastic comment in the introduction to his first article:

“Guido Rocca is clearly setting a precedent with his brilliant, lively journalism, which is somewhat new in style, and we are very happy to make way for young people, even when it comes to writing.” Clerici’s contributions to the magazine continued sporadically until 1951, when Luigi Gianoli, who wrote about horse racing for La Gazzetta dello Sport, suggested Clerici’s name to editor Gianni Brera. The latter, who for Clerici was “the only great writer who did not find it demeaning to cover sports in a country victimized by rhetoricians and literary lobbies” (story Il Cavaliere, in Una notte con la Gioconda [Ver]), established a special bond with him, which translated into years and years of brotherly friendship and collaboration. Clerici continued to write for La Gazzetta until 1954, when Brera was forced to leave his position due to a disagreement with the owners. The two then joined forces and founded the weekly magazine Sport Giallo, which Clerici described as “a less perverse Guerin Sportivo.” The project, which lasted only a couple of years, must have suffered from fierce competition and organizational instability: “[Brera] had found a couple of admirers-financiers. The two of us did all the work on the newspaper. Sport Giallo certainly did not generate large profits. The others collaborated from outside and signed, I think, with pseudonyms” (Enrico Currò, Mario Fossati e la storia del giornalismo sportivo in Italia (1945-2010) [Mario Fossati and the history of sports journalism in Italy (1945-2010)], Bolis Edizioni, Azzano San Paolo (BG), 2018).

A splendid misunderstanding (1956-1987)

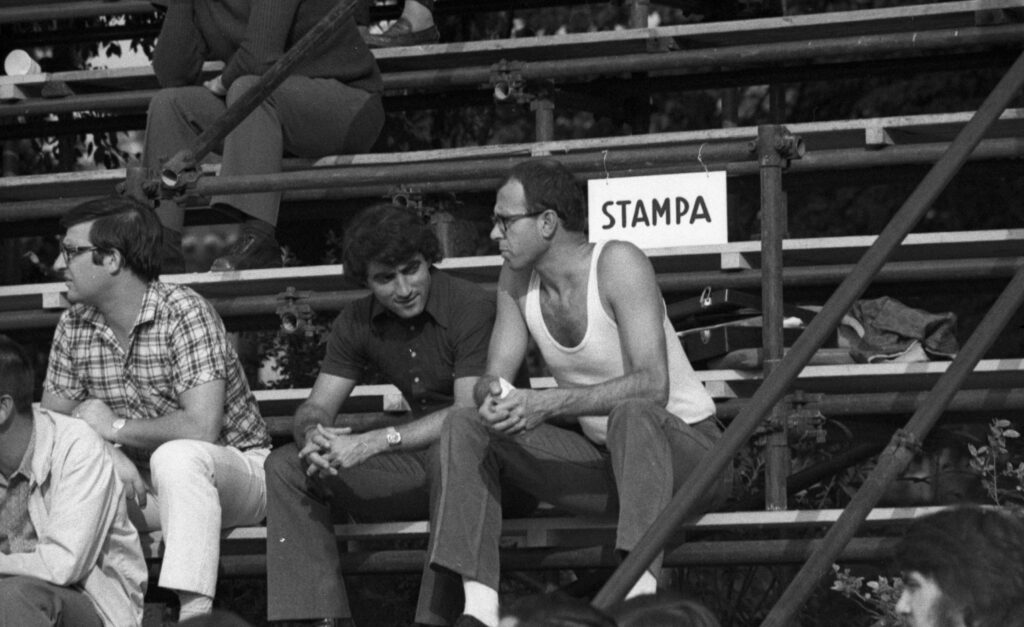

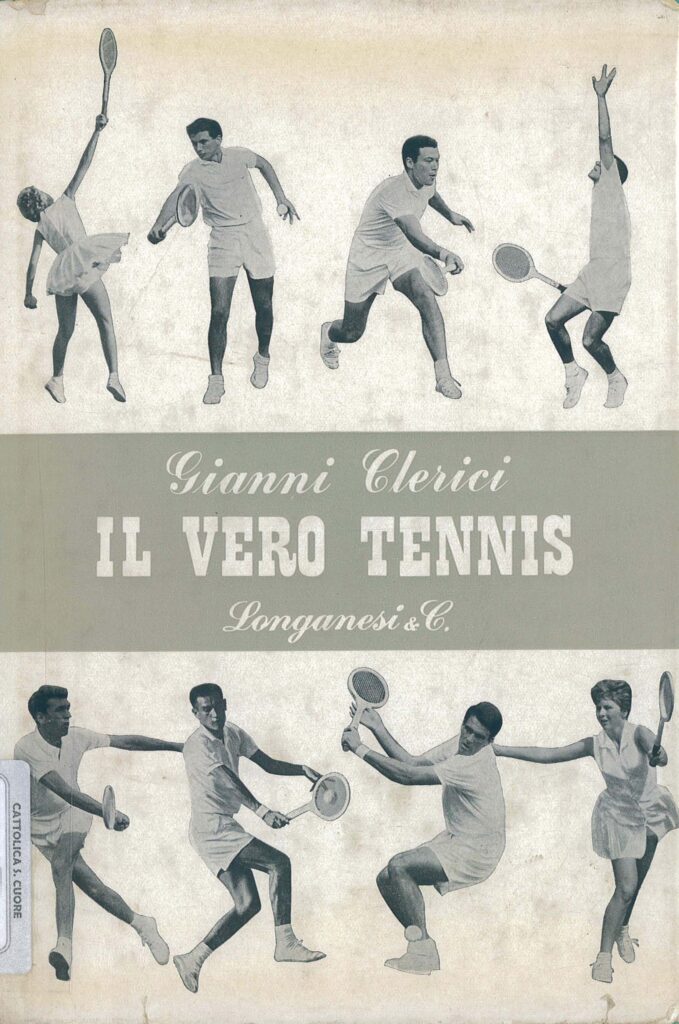

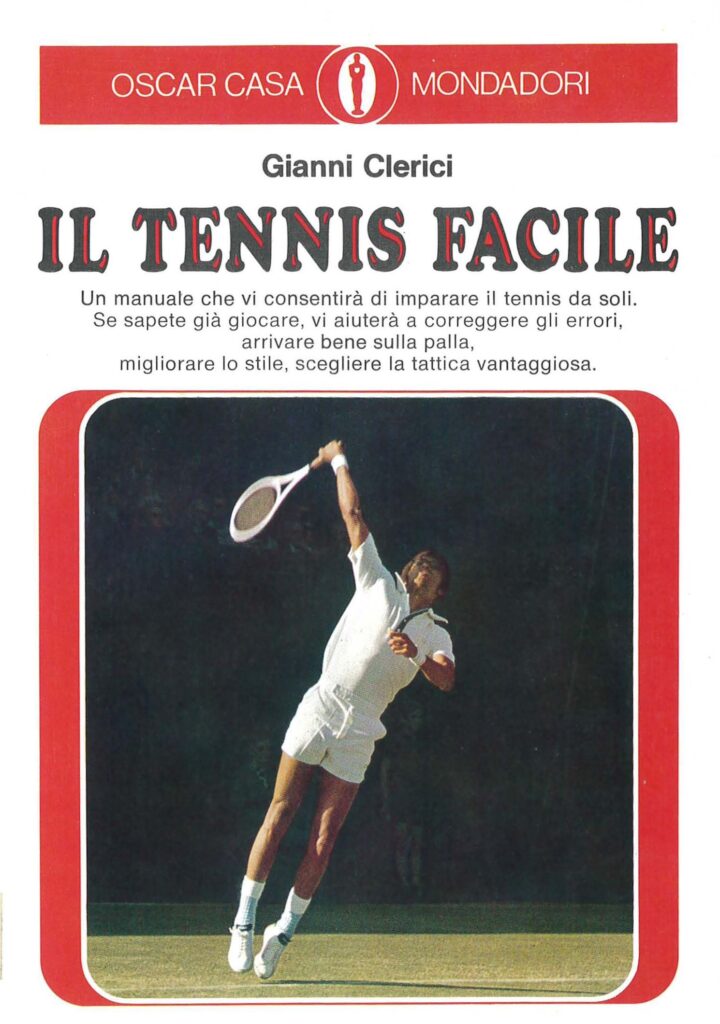

1956 was the year of the turning point: the then ENI president Enrico Mattei founded the newspaper Il Giorno in Milan, to counterbalance the overwhelming power of Corriere della Sera. As editor-in-chief of the sports section, editor Gaetano Baldaccichose Gianni Brera himself, who decided to take Gianni Clerici with him: “We went as a group to Il Giorno, hanging on Brera’s tail. […] I went there, but it was not that I wanted to be a journalist” (Enrico Currò, Mario Fossati…). What took shape was an exceptional young team, considered by many to be the non plus ultra of sports newsrooms: Mario Fossati at cycling, Giulio Signori at athletics, Franco Grigoletti at basketball and, indeed, Gianni Clerici at tennis. Yet, with his usual irony, Clerici often downplayed the value of his time at Il Giorno, calling his career “a great misunderstanding, in what is mysteriously considered the reference editorial office of Italian journalism: it must be because the many sports editorial offices of all time are of a discouraging level” (Enrico Currò, Mario Fossati…). During his more than 30 years of collaboration with the newspaper, his contributions are not limited to tennis reports, but embrace a wide variety of disciplines: “I began as a correspondent […]: Giro d’Italia, Tour de France. I did my tennis stuff, for which I had been taken to the Gazzetta dello Sport when I was nineteen by Gianni Brera, who was sort of my elective uncle. And then I had the basketball column, because I played all sports, I played basketball. I had the skiing column, especially, because I was a skier”(interviewed by Rivista Studio in 2012). Starting with the Rome edition in 1960, he even followed the Olympics. “The tennis guy,” a definition Gianni was often saddled with during his career, thus does not fully describe his involvement in the world of journalism, especially if one considers his off-court contributions: from travel reports to places he visited for tournaments to lifestyle columns in the Sunday Rotocalco. His first essays also belong to this period: The Real Tennis (Longanesi, Milan 1965), (Il tennis facile Oscar Mondadori, Milan 1972) and Il grande tennis (1978).

In 1974, Mondadori published the first edition of his masterpiece, 500 Years of Tennis, “the best-selling Italian book abroad after The Divine Comedy and Pinocchio,” as Enzo Biagi ventured to say. It is a veritable “bible” of tennis, an international success translated into six languages. To write this universal history, Gianni Clerici drew on materials preserved in the British Museum, which he frequented assiduously in the 1960s during his time in London as deputy correspondent for Il Giorno. The detailed statistical tables relating to players and tournaments are compiled by my friend Rino Tommasi, nicknamed “ComputeRino” by Clerici due to his infallible memory.

Between chronicles and laurels (1987-2022)

Nel 1987 arriva la chiamata di Eugenio Scalfari, che porta Gianni Clerici a la Repubblica, dove si ricongiunge con Brera e Fossati, trasferitisi nel 1982: nello stesso periodo inizia anche la collaborazione con L’Espresso. Sulle colonne di Repubblica gli viene concessa piena libertà per raccontare il ‘dietro le quinte’ del mondo dello sport e non solo: famosi sono i suoi profili di campioni, a cominciare dal primo memorabile articolo, dedicato a un matrimonio parigino dove a distinguersi è l’eccentrico tennista rumeno Ilie Năstase, presentatosi “in calzoncini corti e scarp de tenis”.

Risale agli anni Ottanta l’esordio televisivo: sugli schermi di Canale 5 fa capolino la strana coppia Gianni Clerici-Rino Tommasi, che importa in Italia il modello americano della telecronaca a due. The formula quickly proved to be a success: in the following years, the Clerici-Tommasi duo moved to TelePiù (later Sky) and continued to commentate on Grand Slam tournaments until 2011.

In general, the new millennium has been very rewarding: in 2002, Clerici published Divine. Suzanne Lenglen, the greatest tennis player of the 20th century (Corbaccio, Rome), a biography dedicated to the iconic French athlete, the author’s favorite. In 2006, he was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport for his long and distinguished career as a journalist and commentator in the field:

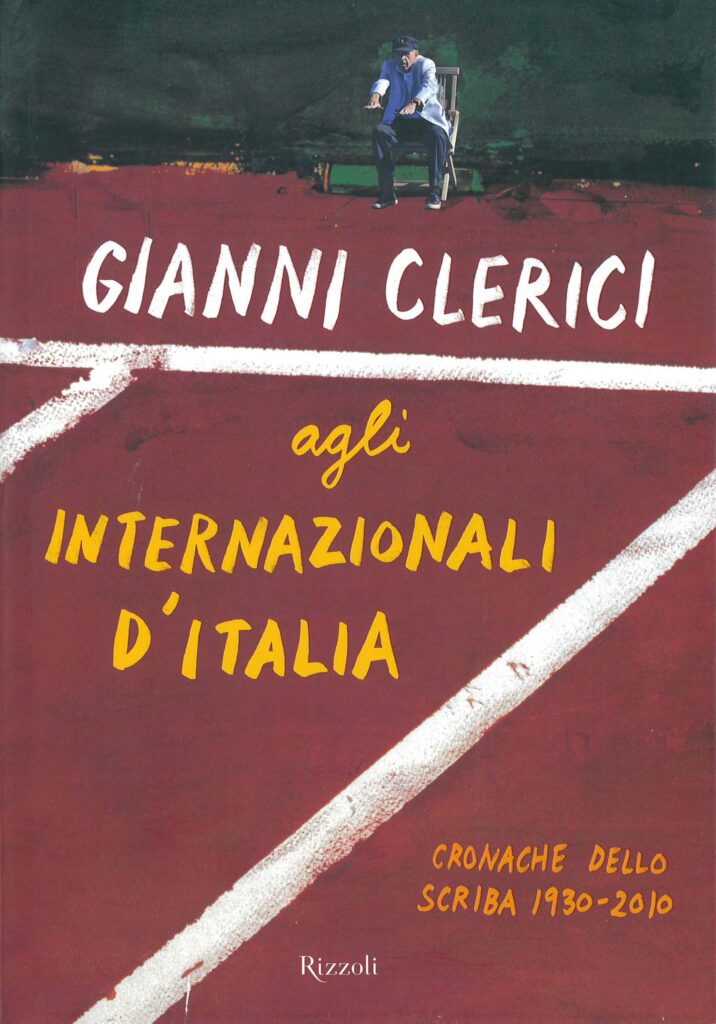

In 2010, a collection of articles entitled Gianni Clerici at the Italian Open. Chronicles of the scribe. 1930-2010 (Rizzoli, Milan). In 2013, it is the turn of Wimbledon. Sixty years of history of the world’s most important tournament (Mondadori, Milan). In 2018, Mondadori published Tennis in art. Stories of paintings and sculptures from antiquity to the present day.. It is from 2021 Tennis made easy. Illustrated manual for beginners and enthusiasts of the game (Baldini e Castoldi, Milan), an updated guide written together with Riccardo Piatti, whose illustrative photographs depict a red-haired boy: Gianni’s career, which spanned more than 90 years, allowed him to recognize the crystal-clear talent of that young man, the same Jannik Sinner who, a few years later, established himself on the world tennis stage with triumphs in the Davis Cup and the Slams.

Gianni Clerici died on June 6, 2022, leaving behind an intellectual legacy that is difficult to match: more than seven thousand articles and some thirty novels, plays, poetry collections, and essays. After his death, his family decided to donate his archive and library to the “Raccolte Storiche” Documentation and Research Center at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Brescia. Mediaset also reported the news of the donation with the report An inimitable talent: Gianni Clerici in the evening magazine program Studio Aperto Mag.