‘Er Francia’ shines in Paris: Nicola Pietrangeli becomes Slam champion

Gianni Clerici was perhaps the world’s greatest expert on Nicola Pietrangeli, so much so that he once even refused to write his biography, as he himself said. He knew him so well that he could discuss every single technical gesture that came from the skillful hands of that tennis prodigy, Nicola. Gianni had been there from the very beginning, when a sixteen-year-old Nick at Tennis Parioli stunned him with a couple of backhand passing shots that already foreshadowed his brilliant future. The Roman youngsters at the time, noting his French accent from his Tunisian childhood, had nicknamed him ‘Er Francia’.

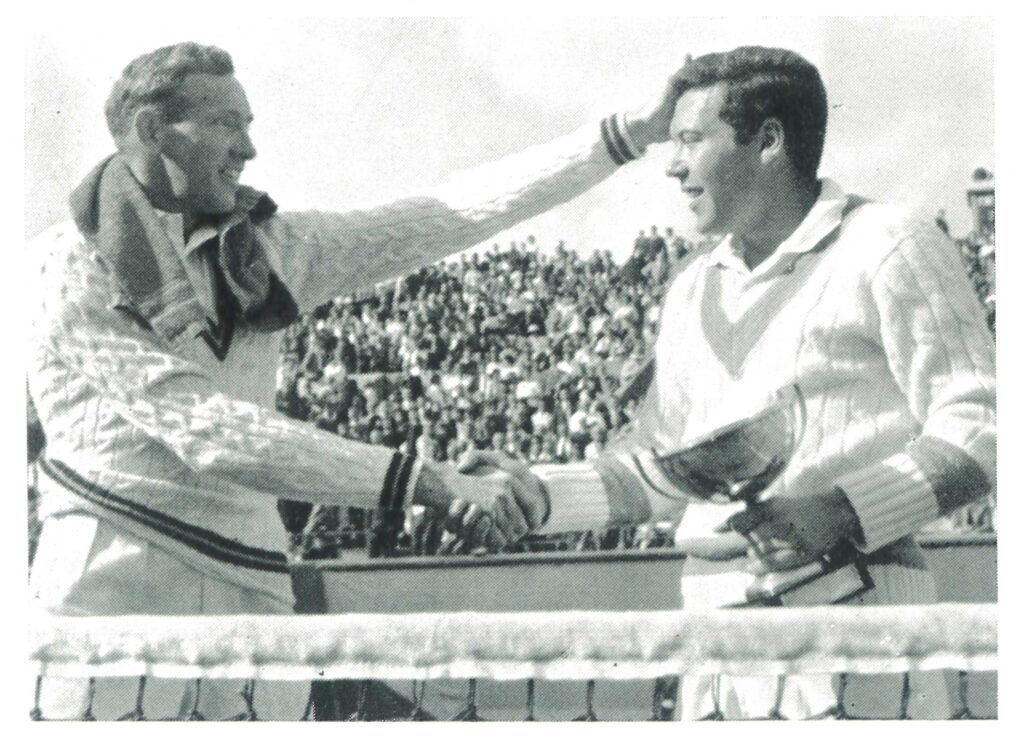

Gianni knew him very well; yet, when his crowning moment came—Saturday, May 30, 1959, the day he defeated South African Ian Vermaak to raise the Roland Garros trophy under the sunny Parisian sky—Gianni was not in the stands. Clerici later explained this absence in a 2013 interview with La Repubblica on Pietrangeli’s eightieth birthday: “Think about it: as a young correspondent for Il Giorno, my beloved editor Italo Pietra didn’t consider the trip important,” during which Pietrangeli would achieve “a victory against the little-known South African Vermaak, whose serve-and-volley had been overwhelmed by Nicola’s passing shots.”

Paris, 30-05-1959, Roland Garros Final: Nicola Pietrangeli – Ian Vermaak 3-6; 6-3; 6-4; 6-1

As striking as it is, this absence in Clerici’s archives allows us to read the narration of that historic first Slam victory by an Italian from another perspective: that of the period editions of Il Tennis Italiano, Italy’s leading tennis magazine, and Tennis de France, its French counterpart. Starting with the latter, we can briefly analyze the stylistic choices of the two publications.

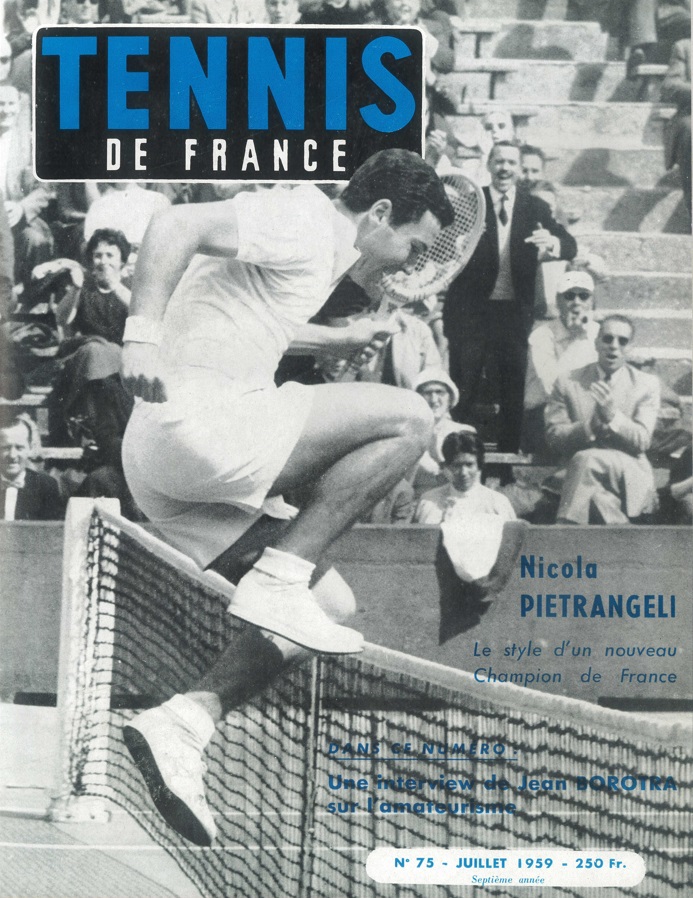

First, Tennis de France dedicated the July 1959 cover to the native of Tunis, showing Pietrangeli leaping over the net—a gesture symbolically crossing the physical and mental boundary separating him from his opponent—before congratulating Vermaak, the tournament’s great revelation. This iconic leap, far from trivial, was the last in a series of gestures that had made Pietrangeli extremely popular in France, beyond his origins: so admired that the first article dedicated to him, written by Henri Gault (later famous for gastronomic guides), crowned him as “Fantaisiste – Brillant – Follement doué et charmant” (whimsical – brilliant – wildly gifted and charming).

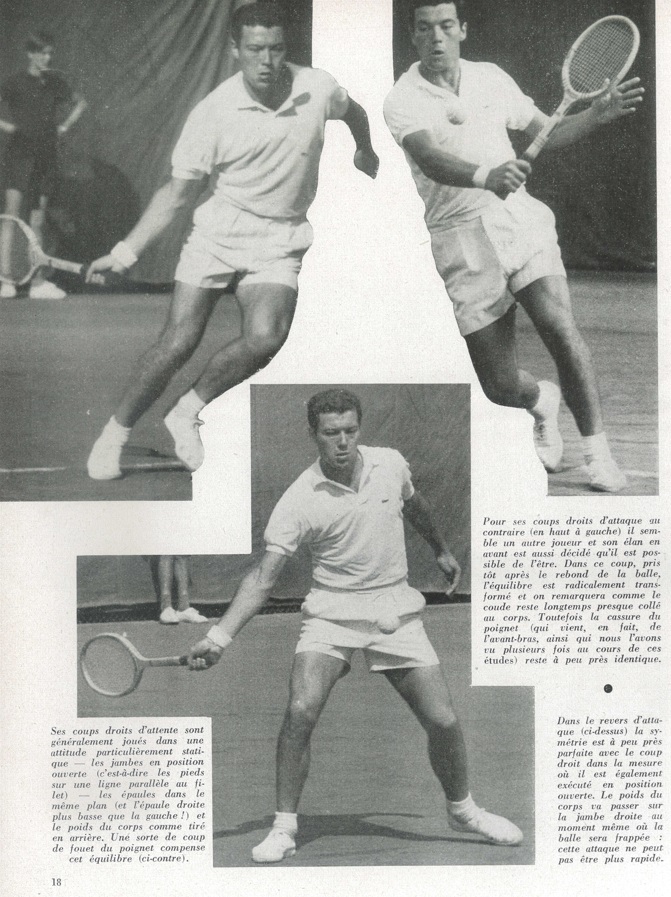

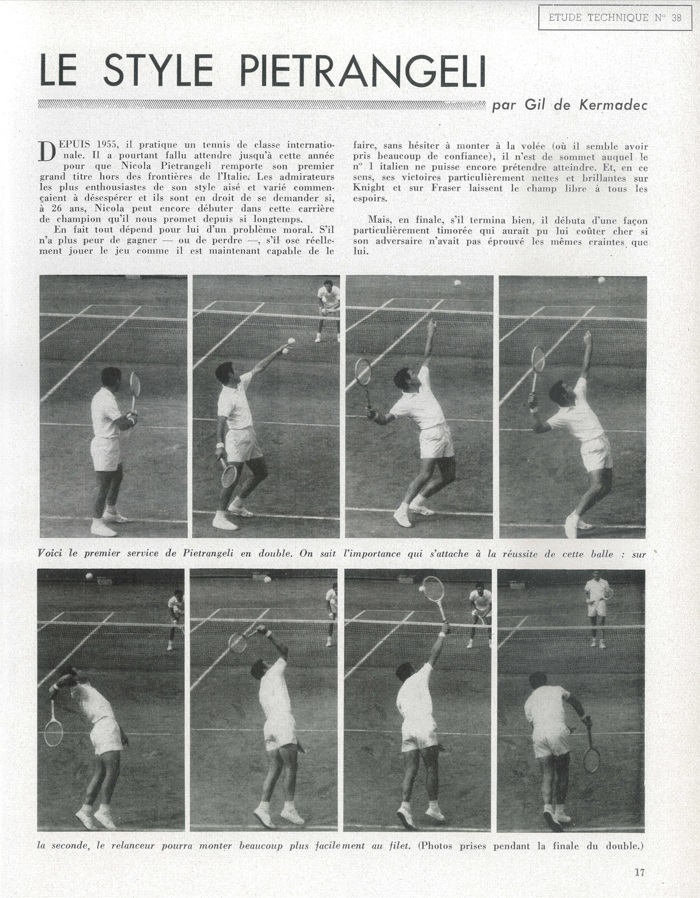

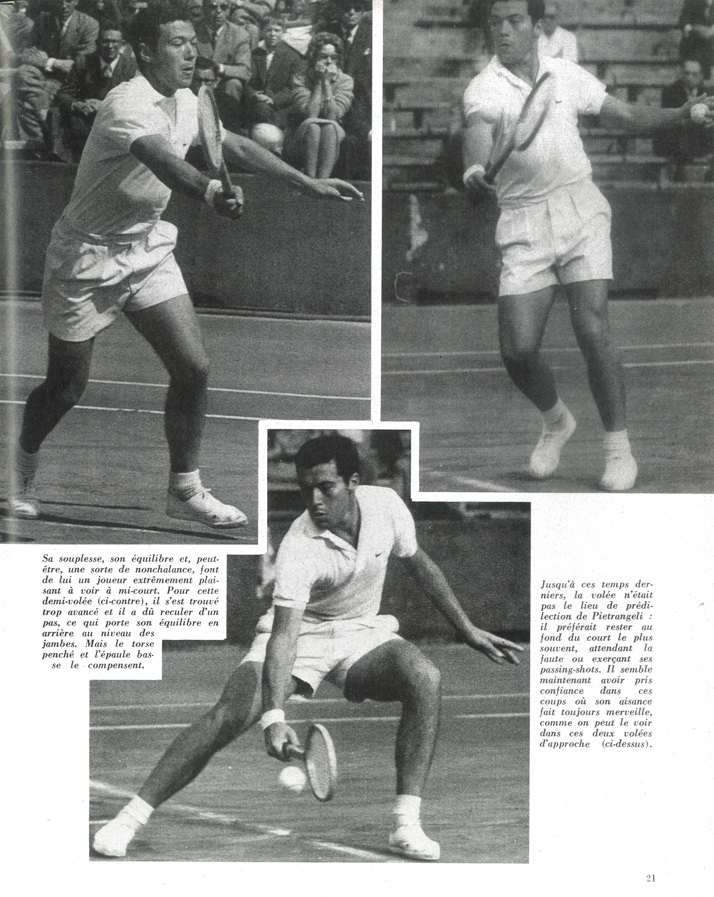

The following article, by the magazine’s editor-in-chief Gil de Kermadec (whom Clerici did not hesitate to call a genius), was a splendid tribute to Pietrangeli’s game, described in a detailed technical study titled Le style Pietrangeli, supported by very precise photographic captions. The Italian’s tennis was here defined as “de classe internationale,” mainly because “sa souplesse, son équilibre et, peut-être, une sorte de nonchalance, font de lui un joueur extrêmement plaisant à voir” (his suppleness, balance, and perhaps a certain nonchalance make him an extremely pleasant player to watch).

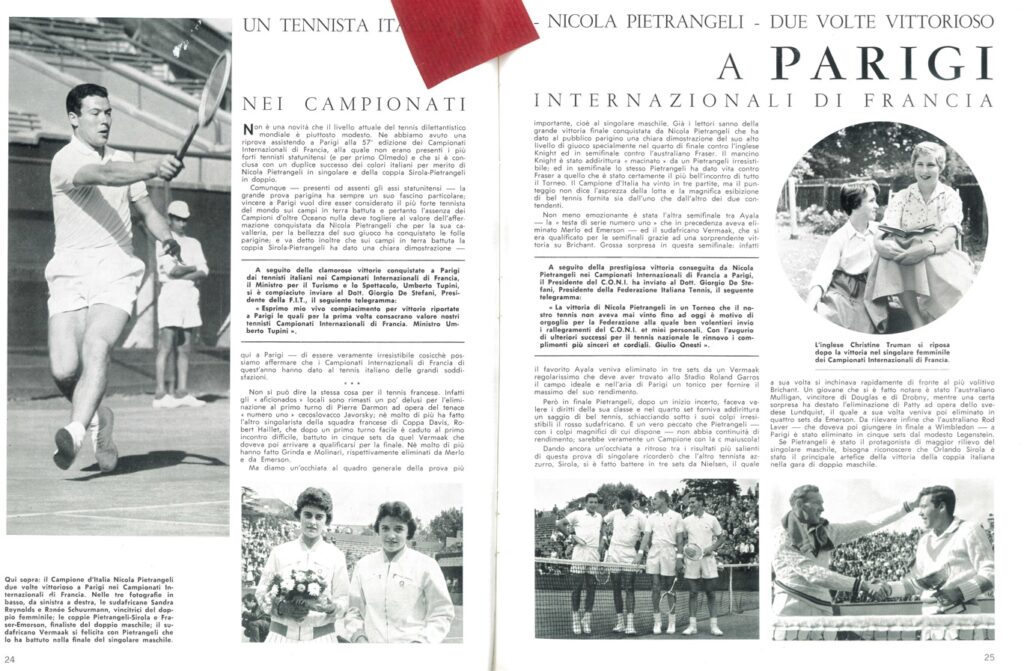

Turning to Il Tennis Italiano, in the July-August 1959 edition, the focus shifted to the exceptional feat of a Pietrangeli ‘twice victorious in Paris,’ both in singles and doubles alongside Orlando Sirola. Paradoxically, despite the Italian triumph, the tone was not overly celebratory. The lead of the report by Chantal Kuntz read as follows:

It is no novelty that the current level of amateur tennis worldwide is rather modest. This was proven once again by attending the 57th edition of the French International Championships in Paris, which did not feature the strongest American players (notably Olmedo).

The critique was soon softened by the clarification that “the absence of the overseas champions does not detract from the value of Nicola Pietrangeli’s achievement, who with his chivalry and beautiful game conquered the Parisian crowds.”

Finally, there is the curious special article “How I Won Paris,” authored by Pietrangeli himself, which includes a humorous anecdote about the post-tournament celebrations:

The celebrations for my title cost me all my prize money. Before the Championships, I had promised some friends that if I won, they would be my guests for a dinner of caviar and champagne. Well, they all remembered, those fine folks; fifteen showed up on Sunday evening. At the ‘Crazy Horse,’ where I am a regular, the owner treated us; but later, at the ‘Club de l’Étoile,’ I had to pay. The caviar consumed wasn’t much, but the champagne flowed like water. Sirola, who hadn’t bet anything, paid for only one bottle.