Wimbledon 1960: Diary of a ‘giornatore’

Journalist or writer… writer or journalist… why choose? Welcome the ‘giornatore’!

Gianni Clerici, despite those who thought they could pigeonhole him, decided not to split himself in two, but to double himself — and for this, we will be eternally grateful. He loved calling himself a ‘giornatore’ because the extra edge of his pen lay precisely in his ability to merge two parallel worlds, often mutually impermeable: on one side, his newspaper articles, which became cult objects for their unpredictable narrative twists and that cultured, rarefied atmosphere; on the other, his novels, infused with traits typical of journalism, so much so that the narrator’s gaze seemed that of a correspondent, poking around behind the scenes of events and reporting their most hidden details.

The perfect opportunity to grasp Clerici’s writing talent is offered by the Wimbledon tournament, the tennis competition par excellence and the oldest in the world. The edition in question is that of 1960, when the Australian Neale Fraser won the men’s singles title by defeating his compatriot Rod Laver in the final, who had just come from a legendary semifinal against our own Nicola Pietrangeli: it is precisely this last match, which ended in the fifth set, that is the focus here, where we will see Gianni Clerici at work first with his newspaper article and then with his novel.

On June 29th, in the pages of Il Giorno, he recounts some key moments of the Pietrangeli-Laver duel as follows:

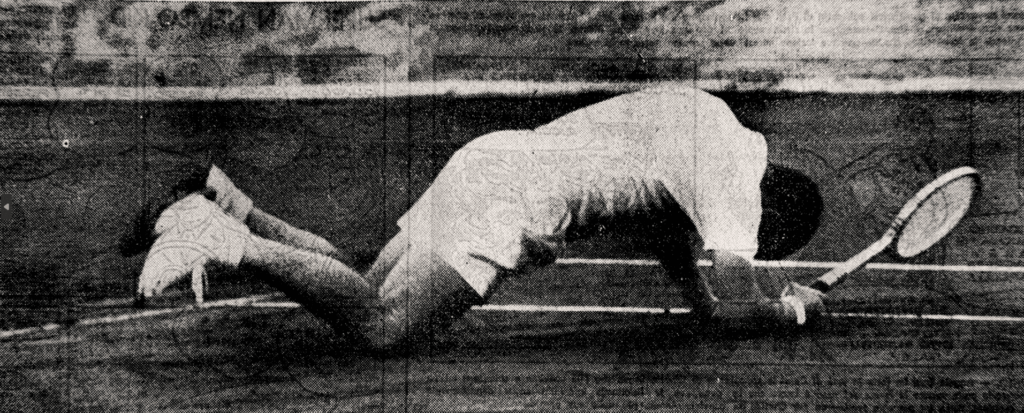

Pietrangeli lost to Laver the chance to win Wimbledon: he lost it by being aware of it, while the Australian struggled to defend himself without having time to think, to be afraid, to suffer like Nicola when the game slipped from his hands and the wind carried the ball to unforeseen whims. […] But with the wind Laver throws himself forward and Nicola’s game becomes icy, shatters. […] Nicola gets angry, fires three passing shots that Laver catches while somersaulting: he loses the point on the fourth, and our guy makes a Trastevere-style gesture, sending him to hell. […] And then comes this damned fifth set: Nicola has Laver in his hands and he slips away with brilliant inventions.

These are confident brushstrokes, delivered by Clerici with vivid, almost sensory and tactile writing, so much so that the match remains imprinted on the page and can be clearly felt.

The style adopted in the literary counterpart is different, more elegant and measured: we find ourselves in the novel Londra 1960, which, together with Costa Azzurra 1950 and Alassio 1939, forms the triptych titled The White Gestures, one of Clerici’s most emblematic works as a writer. Here the author unleashes his poetic vein and brings to life emblematic images, moving page by page on the grass of the lawns in front of the Centre Court, “among families enjoying picnics, ladies with their incredible flowery hats, overly well-dressed gentlemen, children in colorful blazers.” The match is described through brief, extremely suggestive flashes, almost like small little poems embedded in the fabric of the narrative:

Look at Nicola with his watery little eyes, Laver, beneath the reddish tuft: he screws the tip of his right foot into the yellowed grass; and uses it as a pivot to rush to the net behind the spinning ball, elliptical in shape from the effect.

Nicola awaited that projectile hopping, frees his arm in a wide backhand swing, and the ball pierces a blade of sunlight along the sideline while Laver throws himself, propping himself up with his right hand to avoid falling, and ends up pirouetting on himself while the crowd applauds […] Laver served a first ball that cuts the air like a whip. Nicola tamed that killer ball, kept its trajectory low, so much so that Laver almost stumbled.

The match’s outcome does not smile on Pietrangeli, who nonetheless manages to maintain his proverbial composure and does not lose that humble and noble bearing alike, which made him a beloved champion both on and off the court, as Clerici’s chosen words show: “Nicola shows all his good grace, embraces Laver, bows to the Duchess of Kent as if apologizing for not having done better.”

London, June 29, 1960, semifinal: Rod Laver – Nicola Pietrangeli 4-6; 6-3; 8-10; 6-2; 6-4.

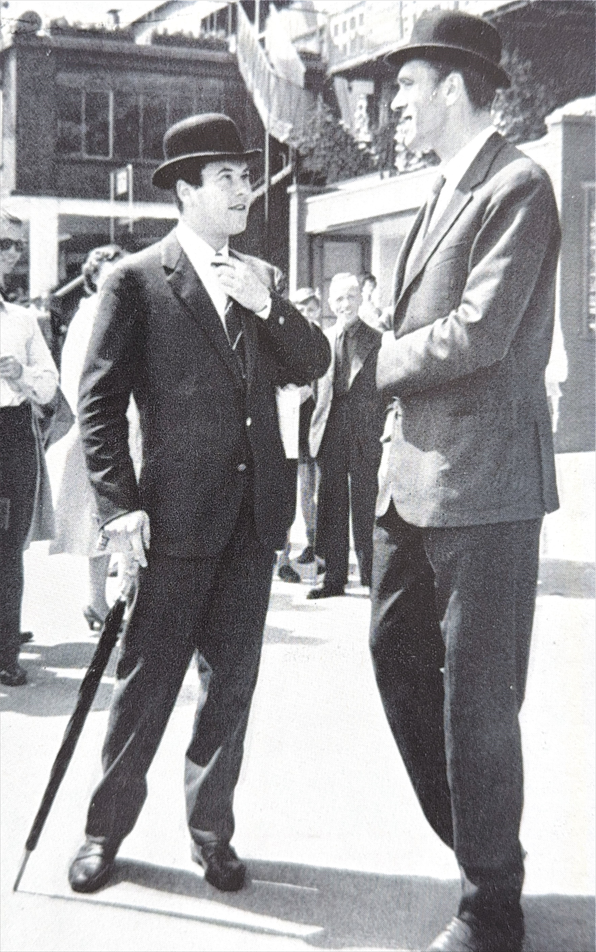

Also at Wimbledon, a couple of weeks later (July 15-17), the European zone semifinals of the Davis Cup between the British hosts and Italy, featuring Nicola Pietrangeli and Orlando Sirola, would be played. In the pages of Il Tennis Italiano at the time, there appears a charming photograph depicting the two Italian athletes in elegant attire, perhaps engaged in an ironic conversation about the strict dress code in place in London, particularly within the gates of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club.