Word from the ‘Little Scribe’

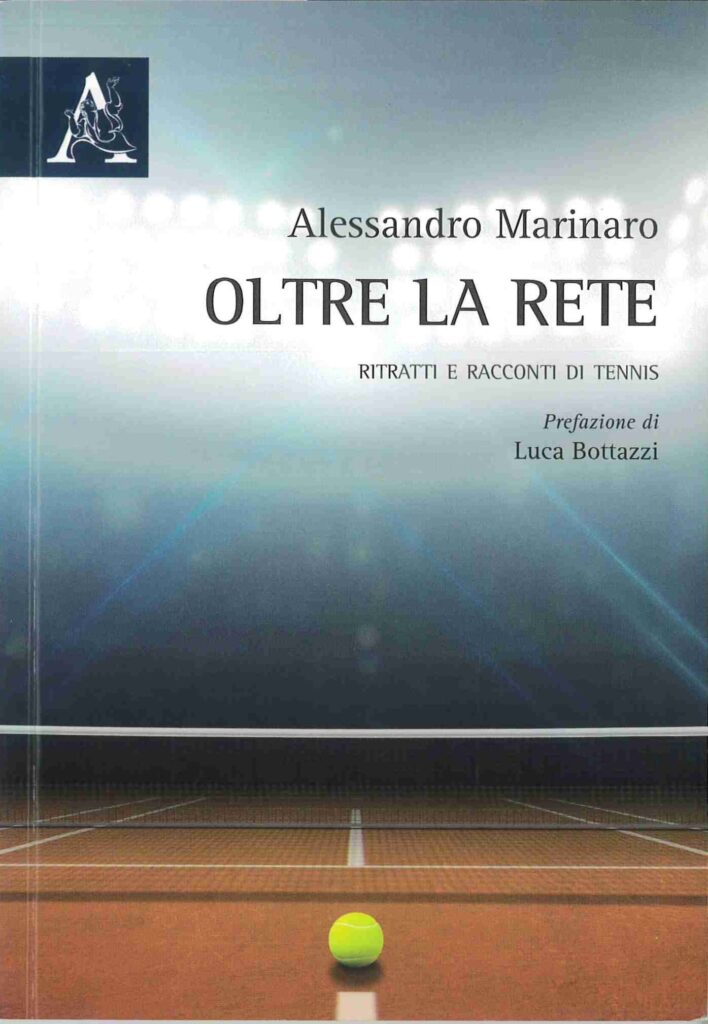

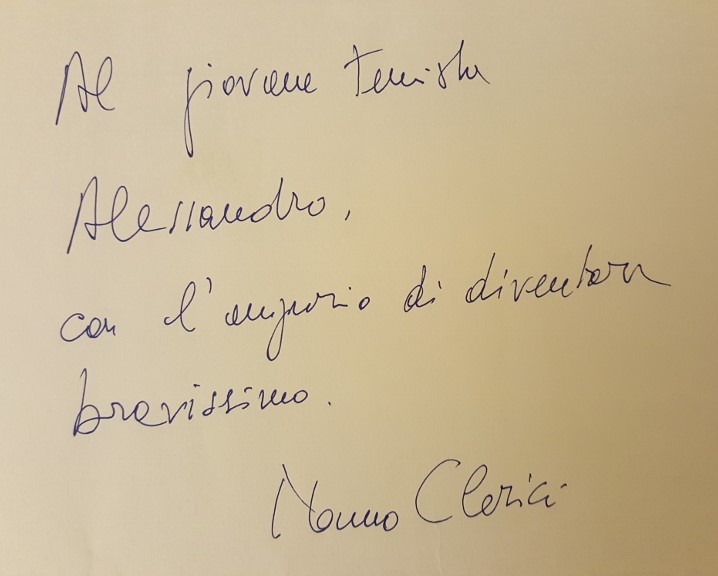

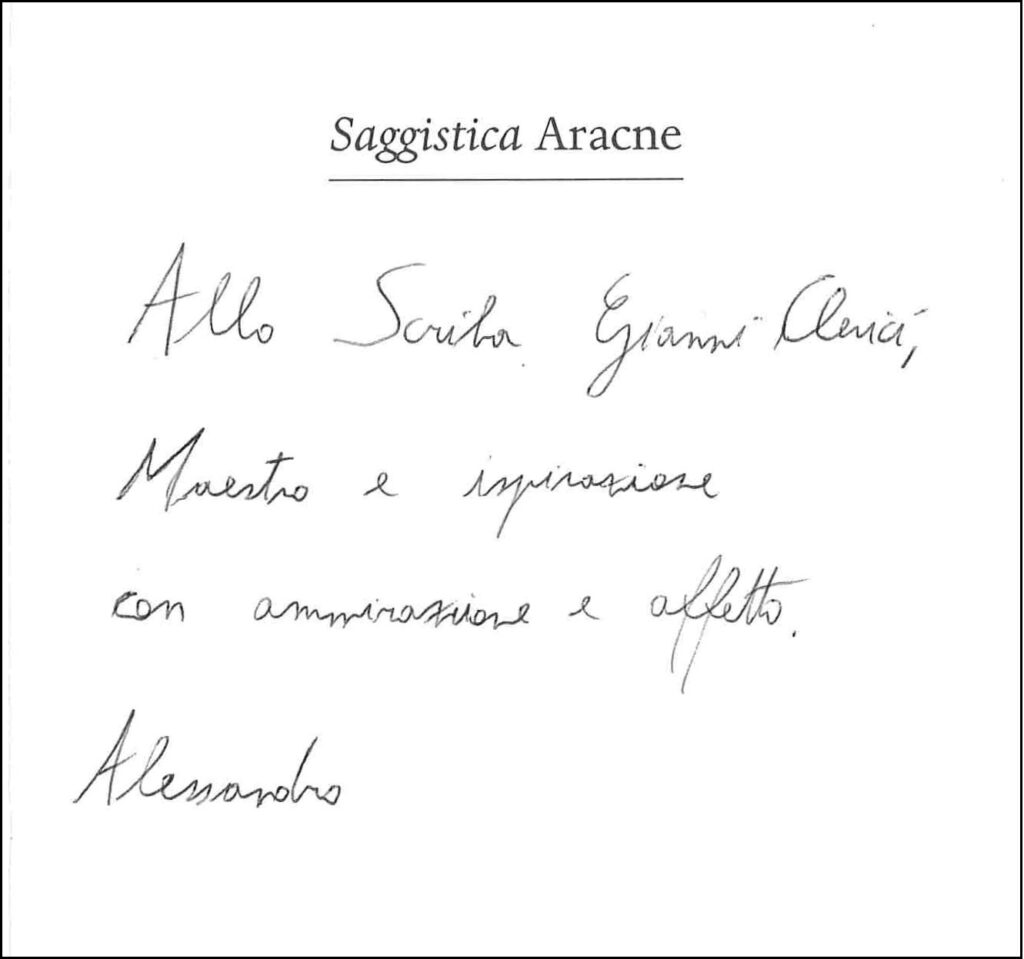

Today, July 24, 2025, Gianni Clerici would have turned 95. To honor his memory, we are publishing the beautiful tribute written in English by Alessandro Marinaro in 2022, shortly after his passing. Alessandro is a great tennis enthusiast and a fan of the Clerici-Tommasi duo. He first met Gianni at the 2007 Italian Open when he was only eight years old, receiving a tender dedication signed ‘Nonno Clerici’ from him. The two would meet again at the Foro Italico for the 2016 edition, where Alessandro had the chance to present some of his articles and stories to Gianni, earning the title of ‘little scribe.’ Many of those texts were published by Aracne in the volume Oltre la rete. Ritratti e racconti di tennis , preserved in the Clerici Collection, with a dedication from the author to the Scribe.

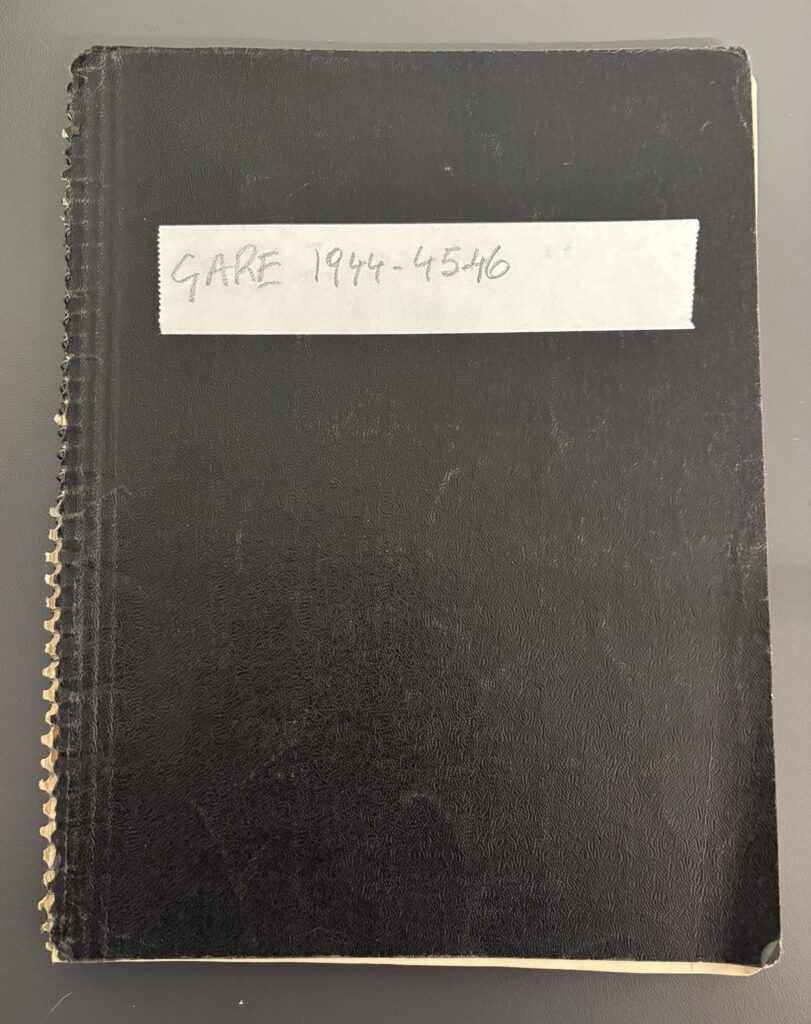

We like to think that in him, the elderly Clerici saw a part of himself, the young man who, as a teenager, wrote his first tennis reports in a notebook dating from 1944-1946, which we preserve with great care, along with other documents related to his journalistic beginnings.

Remembering The Greatest Loser Ever Seen: An Encounter with Gianni Clerici

Rome, May 11, 2016. A personal recollection of a conversation with the late Gianni Clerici, legend of sports journalism and tennis hall of famer, as seen through the eyes of a (then) seventeen-year-old freelance. Player, intellectual, genuine art lover and collector, novelist, playwright, poet. Very few other figures have personified the art, ideas, style, and culture that surround tennis as Mr. Clerici has in his life.

Alessandro Marinaro

Although some may disagree, there’s one week of May in which Rome’s Foro Italico becomes the second-most enchanted, suggestive place on tour, right after the All-England Croquet and Tennis Club, and it’s not that difficult, after all, to see why one may get this feeling while entering its gates.

Set against the green slopes of Monte Mario, the Foro is the smallest venue to figure in the golden ring of Masters. Its atmosphere suspended in time and its tight spaces are reminiscent of Wimbledon for how they close the distances between fans, players, the press, the tournament staff, and simple onlookers. Everyone gets to walk the same narrow alleys between courts, to eat in the same places. Ball kids, qualifiers, top seeds, fans, reporters, photographers, umpires, line judges.

It remains one of the few places on tour where one really still gets the impression that anything can happen, on and off the court.

On top of that, beyond the times in which the Internazionali have been christened as the hypothetical “fifth major” (should there be one) in no other places I have seen the same hunger for ground tickets as in Church Road and the Foro.

Unlike Wimbledon and its restful tones of green, however, the Foro thrives on the sharp contrasts of its color palette. Between the soothing, deep green of giant pine trees caressed by the wind, or the gentler green of hedges encircling courts, and the burning red-orange clay of courts inflamed by sunlight. The spotless, violent white of stone and marbles, bleachers and statues pitched against bright blue skies. Scorching heat until dusk, cold and damp during night sessions.

Around noon, and maybe on that day in particular, even white marbles looked featherlight. Going in, I had the feeling even those could have evaporated under the sun.

The meeting had been set for lunchtime; one o’ clock sharp.

I had received Mr. Clerici’s phone number nearly one week earlier. As a seventeen-year-old junior freelance working with an online tennis magazine, I had exchanged a few emails with Mr. Clerici himself in the months preceding the tournament.

Strangely enough, the story of our first and last meeting had started with the daring idea of submitting to his judgment one of first pieces for the magazine.

With the benefit of hindsight, “daring” sounds nothing short of an understatement. Just ten years earlier, Mr. Clerici had become one of the only two Italians ever introduced in International Tennis Hall of Fame, together with Nicola Pietrangeli, and the only journalist.

Apart from that, one could have had a more than reasonable fear of his legendary sense of irony. His clashes with the BBC direction during the broadcasting of Wimbledon had turned into a longtime classic, just as his prowess in the subtle art of critique, be it of Federer’s backhand tactics, of a novel or a painting. A virtuosity which elegantly wrapped a much hard-to-find, at times brutal, intellectual honesty.

Fortunately, his replies had not only been elegant as ever, but also a lot kinder than the ones he routinely expressed on Federer’s backhand tactics, at least during the first two sets of Wimbledon’s 2008 final.

One of the last emails had been clear enough for me to jump off my chair.

“If you’re coming at the Internazionali I would like to meet you for a chat. Once you will be there, look for me in the press room. Within the limits of my (alas, non-tennis-related) commitments, plus a small job at the Foro, I really hope to be able to make it. Shouldn’t this happen, please, do not judge me as rude, since the current one is a moment of fatigue.

See you soon, I hope.

Clerici”

What could I have ever said? I hurried to book my train ride for the week after, completing the picture with a ground ticket for a mid-tournament day.

Passing along the majestic pine trees separating a row of courts from the Grand Stand, I peeked over Sam Stosur’s kick serve, a couple of volleys from the Bryan brothers, Carla Suarez Navarro’s one-handed backhand. After working my way through packed practice courts and sponsor stands, I could glimpse, beyond the statues of the Pietrangeli, the dark silhouette of the center court.

One o’ clock, at the tables under the off-white gazebo to the left of the stadium.

Shortly after I drew near a steward with a black cap and polo shirt.

“Sorry, I have an appointment with Mr. Clerici”

A voice emerged from behind the low hedges surrounding the tables and the gazebo.

“Yes, we have one, indeed!”

There was no need for the man sitting on the white bench seat to turn. It was him.

“Come, have a seat please”

He went on while the steward handed me a tournament pass.

Mr. Clerici (who repeatedly urged me to call him Gianni) sat in front of me, as the thin fingers of his right hand played with the black necklace of the tournament pass, which dangled over a dark blue blazer and a large, blue and white striped button-down shirt.

“Tell me Alessandro, do you also play tennis right?”

I briefly hesitated.

“How do you play your backhand? One hand or two?”

“Two” I was all-too-familiar with his opinions on the poor aesthetics of two-handers.

“Well, that’s too bad… You’re not to blame though, it seems to me they don’t teach it anymore… or hardly so”

The blazer and shirt looked, as it had always appeared to me on tv and in photographs, way too large on his slender frame, at least one or two sizes too big. I don’t remember asking him, but I could have sworn that was a deliberate style choice, just as the oversize corduroy jackets with patches I had seen him wearing in a 90’s tv show or the white cloth one he had worn in Newport, during his induction in the Hall of Fame.

He continued.

“Listen, I only manage to use my laptop as an Olivetti Lettera 22, but I have read the articles you sent me. Without being professor of anything, I believe you could safely turn into a scribe”

That was how he defined his art and profession: scribe (scriba in Italian). Not coincidentally, the same word indicating the literati of Ancient Egypt, an intellectual elite entrusted with the custody of the written word.

“Regrettably I have never learned, despite owning a house in London, to write in English, which I consider the Latin of our times. Thing which I warmly advise you to do if you have the chance… Look, I’m nearly eighty-six, but if my memory serves, I think you could start with The Readers’ Companion to the Twentieth Century Novel… then one must be lucky enough not to meet mediocre editors… and, in all honesty, I don’t know what the future holds for that strange human category called “journalists”…”

I thanked him, stuttering.

He looked around, crossing his legs.

“I don’t mean to dampen your spirit but, in my long life, I have had hundreds of articles and -still today- one novel, trashed by editors…”

“…”

He paused.

“And tell me Alessandro… who are editors? Failed writers or great critics?”

I do not dare to report here my answer to that question.

“I’m afraid you could, indeed, turn into a writer… Well, I tried… but you see, my father was a businessman… and without my inheritance I would still be having troubles making ends meet…”

“…”

“It all depends on what you want to do… Journalist? Writer? Thanks to that inheritance, and perhaps to my laziness, I could take the liberty of becoming something in-between… If not, I would have probably had to be an actual reporter, or to be stuck on a desk in the headquarters of some newspaper as editor, editor-in-chief, deputy director, director… who knows… I hope you don’t find unsettling these perplexities of mine”.

I knew he had probably been there for Repubblica, the prominent Italian newspaper of which he had been signing the tennis page for nearly thirty years, after spending the previous twenty-five in the Milan-based Il Giorno. He had an atypical relationship with newsrooms and tv broadcasters, as his masterful artistic eclecticism, economic independence, and status in the world of tennis guaranteed him a privileged position from which to enjoy an unusual degree of creative freedom. Editors knew, as his longtime colleague Ubaldo Scanagatta said, Clerici was a writer and artist “stolen by the sport of tennis” and that the lyricism of his prose had to be left intact as much as possible, with its neologisms, sobriquets, and poetic licenses.

Gianni Cerasuolo, editor at Repubblica and, from 2008 on, in charge of the newspaper’s sport section, once wrote:

“The problem with Clerici was to impose a theme on him. A mission destined to fail. Not that he rejected it out of literary pride or because his snobby character forced him to. It was just that if you suggested something, when for example from the management of the newspaper wanted him to deepen a theme, that he talked about a character or a fact of the news, he went for other paths, such as the racehorse refusing the bridles. “So, Gianni, ok with that?”. Then you got an article that barely contained only one line of what you had asked him. But it also ended on the front page because it simply went on transcendent paths that only he could walk, transforming tiebreaks in short stories”.

He could take the liberty of snubbing newsroom directives just as statistics and, at times, even match results, as numbers could have smeared the flow of his writing.

This year, shortly after his passing away, fellow Hall of Famer Steve Flink also wrote “…Clerici’s daily reports were never as steeped in statistics as many of his fellow writers. Clerici was an extraordinary interpreter of the tennis scene. He would often trust his own impressions over those of the players, and that independence was a central feature of his work”.

I couldn’t agree more with Flink.

Over the next half hour, blessed by the Roman afternoon breeze dampening the heat, we went on talking about some great champions of the past. The world’s first tennis superstars, Tony Wilding with his motorbike and the divine, ethereal Suzanne Lenglen.

Mr. Clerici was actually the author of Divina, one of the (if not the) most complete and best-written existing biography of the French diva. One could even have glimpsed a certain glow in his eyes when talking about her. After lingering briefly upon Marguerite Broquedis, the only other player capable of defeating her in an official match (once, when Suzanne was fourteen!), the conversation moved on to Borotra’s demi-volées, Jack Kramer’s big game, then Lew Hoad and Pancho Gonzales, the two who could never be beaten on their best day.

Closer to our own times, from Bud Collins and Chris Evert’s nicknames, Arthur Ashe and John McEnroe, to the end of wooden racquets and his personal knowledge of Borg’s inner demons.

Among the many stories, one particularly curious one about the silk ties worn by the 1976 Davis Cup team which, on that year, had managed to defeat Great Britain, Australia, and Chile to win the only silver bowl in the history of Italian tennis.

“In my forgetfulness, I recall that the Davis Cup five [referring to Panatta, Bertolucci, Barazzutti, Zugarelli and Pietrangeli] had worn those [the ties] during the final draw against Chile in Santiago… A friend of mine, a throwster from Como had manufactured and printed them… there’s one I still keep at home if I remember correctly…” He said, pointing out with his finger the detail in the black and white picture on the screen of my laptop.

In the picture there were four players sitting beside each other, in light-colored trousers and dark jackets with the embroidered tricolor shield. On their white shirts I could see the navy-blue regimental tie Mr. Clerici was talking about.

“Can you see what’s there in the spaces between the stripes?”

I zoomed in. There were four printed figures holding racquets and playing a sort of imaginary doubles, without any lines or nets, as suspended in a blue silk air. Those seemed to me three men and a woman.

“Can you guess? Those are our friends Madame Broquedis, Monsieur Borotra, Mr. Kramer and Mr. Wilding, playing doubles… That illustration should be also at some page in my book, 500 Anni di Tennis… You can’t see Nicola [Pietrangeli] in that picture, but he was wearing it too… It was a sign of protest against the Italian Tennis Federation and its president, Galgani, for not having protected them enough during the political turmoil which the possibility of playing a Davis Cup final in Pinochet’s Chile caused in Italy at that time…”

Who could have ever imagined a blue silk tie as a sign of protest against anyone?

The images of the iconic Italian Davis Cup duo, Panatta and Bertolucci, Il Cristo dei Parioli e and Pasta Kid, wearing the Fila red polo in Santiago against Chile have been touring the world for nearly fifty years now. And yet, watching Una squadra (“A Team”, based on the book by Domenico Procacci) the recent six-part documentary recounting the 1976 Davis Cup victory from the individual perspectives of the four players, plus Pietrangeli and others, there is no unanimity on the red shirt episode as a fully intentional sign of protest against Pinochet.

“The tennis federation or its president certainly did not distinguish themselves for their courage in protecting the guys on the team while they were being politically attacked from every side, getting death threats for wanting to play that final… the tie was a sign of protest against them even just not being the one they were actually supposed to wear on that occasion”.

“…”

Recalling his words, I now remember about a divergence he and his longtime broadcasting companion, Rino Tommasi, were having with Galgani (still the president of the tennis federation at that time) on Fairplay, a 90’s Italian sports show. Accidentally, the two subjects of the dispute were the responsibilities of the federation in the (then) lack of Italian players in the top 20 of the ATP rankings, together with the long overdue renovation of the Foro.

“It was Nicola that protected them… and I’m pretty sure he still keeps that tie”.

Instinctively, my eye fell on the perimeter of white statues crowning the Pietrangeli, some hundred meters besides Mr. Clerici’s shoulders and his bench seat. I thought back to what happened in Newport ten years earlier, when the man sitting in front of me rejoined Pietrangeli in the Hall of Fame. I also thought that Nicola and Gianni, as different as they could be, eventually shared something much more profound than a Hall of Fame induction and a silk tie. Gianni’s words were featherlight, just as Nicola’s backhand dropshots.

What they shared was lightness, the one Italo Calvino famously elevated to a virtue, together with the indispensable amount of indolence and aristocratic detachment necessary to practice it in the modern world. Calvino himself once said about Gianni “…Clerici is one of the greatest writers I have ever known. Unfortunately, he writes about sports”.

As the clock struck twenty past two, I knew our time was almost up.

Clerici glanced around.

“Returning to writing my friend… it really does take good luck… One must have had the right mentors… and also that may not be enough to make a living out of it. I remember meeting Hermann Hesse once, as a boy, without the courage to ask for an autograph…”

“…”

“Then Gianni Brera at Il Giorno, without him I would have never become a journalist… and I still keep, after fifty years, the letters received from Giorgio Bassani and Mario Soldati. Eventually they nominated me for the Premio Strega [the most prestigious literary prize in Italy] … something no one else has ever done again for one of my books”

Only recently I have read that, in his foreword to one of Clerici’s books, back in 1965, the other Gianni (Brera), writer and trailblazer of Italian sports journalism, accused himself of having “…to have instigated a writer of assured talent to journalism”.

“I’m now having troubles with my editor and agent for some question of missed payments and forewords to books by others… It is really a fortune for me that I can survive without this kind of revenues… Writing is a risky business I’m telling you… unless you’ve got a good inheritance to count on…”

“…”

“…at least move away from tennis… If you insist, I remember that Bassani, the one from Il giardino dei Finzi Contini, once told me I should’ve only written about tennis under a pseudonym. I never took his advice… please take it from me”

After that, around half past two, we shook hands and parted. Luckily enough, I found the courage to ask for an autograph and a picture together.

Perhaps I haven’t been wise enough to take his last advice, at least for what concerns the riskiness of writing or the use of pseudonyms, and now that I find myself with one of Mr. Clerici’s novels in my hands, I gesti bianchi (“White Gestures”) I reminisce of my one and only encounter with him.

Still, the best way I can find to remember the Scribe is the last bit of his Hall of Fame induction speech. Writes Steve Flink, “He captured two National Junior doubles titles in 1947 and 1948 as well as reaching the final of the singles in 1950. In his early twenties, Clerici competed in the men’s singles at Wimbledon, making the main draw in 1953 and appearing in doubles on those same British lawns a year later. As well as he may have played the game, Clerici was born to be part of his beloved sport in a different way”.

Mindful of his short-lived career as a player, he presented himself to the Newport crowd by saying “…if I have to represent somebody in front of this incredible group of real champions and tennis players, is perhaps because I could represent the losers… because there is no winner without losers… the losers are not there, they’re all winners… so I said to myself, Clerici, I take you there because you are the greatest loser ever seen in history”

He went on, looking around theatrically.

“…because in between two Roland Garros and two Wimbledon, I never won a single match… and then I think it’s a good reason for my award”.

Ironically, Mr. Clerici pronounced that speech with a navy silk tie, dotted with white player figures.